Dante shown holding a copy of the Divine Comedy, next to the entrance to Hell, the seven terraces of Mount Purgatory and the city of Florence, with the spheres of Heaven above, in Michelino's fresco.

The Divine Comedy (later christened "Divina" by Giovanni Boccaccio), written by Dante Alighieri between 1308 and his death in 1321, is widely considered the central epic poem of Italian literature, and is seen as one of the greatest works of world literature.[1] The poem's imaginative and allegorical vision of the Christian afterlife is a culmination of the medieval world-view as it had developed in the Western Church. It helped establish the Tuscan dialect in which it is written as the Italian standard.[2]

Structure and story

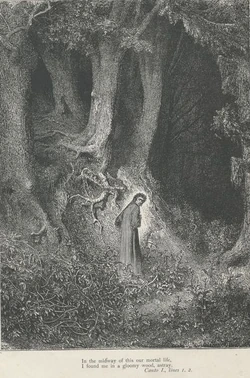

Gustave Doré's engravings illustrated the Divine Comedy (1861–1868); here Dante is lost in Canto 1 of the Inferno.

First printed edition, 11 April 1472.

The Divine Comedy is composed of over 14,000 lines that are divided into three canticas (Ital. pl. cantiche) — Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise) — each consisting of 33 cantos (Ital. pl. canti). An initial canto serves as an introduction to the poem and is generally not considered to be part of the first cantica, bringing the total number of cantos to 100. The number 3 is prominent in the work, represented here by the length of each cantica. The verse scheme used, terza rima, is hendecasyllabic (lines of eleven syllables), with the lines composing tercets according to the rhyme scheme aba, bcb, cdc, ded, ....

Albert Ritter sketched the Comedy's geography from Dante's Cantos: Hell's entrance is near Florence with the circles descending to Earth's centre; sketch 5 reflects Canto 34's inversion as Dante passes down, and thereby up to Mount Purgatory's shores in the southern hemisphere, where he passes to the first sphere of Heaven at the top.

The poem is written in the first person, and tells of Dante's journey through the three realms of the dead, lasting during the Easter Triduum in the spring of 1300. The Roman poet Virgil guides him through Hell and Purgatory; Beatrice, Dante's ideal woman, guides him through Heaven. Beatrice was a Florentine woman whom he had met in childhood and admired from afar in the mode of the then-fashionable courtly love tradition which is highlighted in Dante's earlier work La Vita Nuova.

In Northern Italy's political struggle between Guelphs and Ghibellines, Dante was part of the Guelphs, who in general favored the Papacy over the Holy Roman Emperor. Florence's Guelphs split into factions around 1300: the White Guelphs, who opposed secular rule by Pope Boniface VIII and who wished to preserve Florence's independence, and the Black Guelphs, who favored the Pope's control of Florence. Dante was among the White Guelphs who were exiled in 1302 by the Lord-Mayor Cante de' Gabrielli di Gubbio, after troops under Charles of Valois entered the city, at the request of Boniface and in alliance with the Blacks. The Pope said if he had returned he would be burned at the stake. This exile, which lasted the rest of Dante's life, shows its influence in many parts of the Comedy, from prophecies of Dante's exile to Dante's views of politics to the eternal damnation of some of his opponents.

In Hell and Purgatory, Dante shares in the sin and the penitence respectively. The last word in each of the three parts of the Divine Comedy is "stars."

Inferno

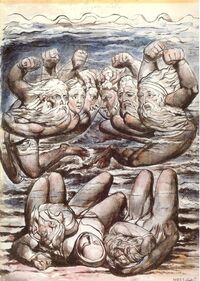

The Wood of the Self-Murderers: The Harpies and the Suicides, c. 1824-7. William Blake, Tate. 372 × 527mm.

The poem begins on the night before Good Friday in the year 1300, "halfway along our life's path" (Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita), and so opens in medias res. Dante is thirty-five years old, half of the biblical life expectancy of 70 (Psalm 90:10), lost in a dark wood (perhaps, allegorically, contemplating suicide—as "wood" is figured in Canto XIII, and the mention of suicide is made in Canto I of Purgatorio with "This man has not yet seen his last evening; But, through his madness, was so close to it, That there was hardly time to turn about" implying that when Virgil came to him he was on the verge of suicide or morally passing the point of no return), assailed by beasts (a lion, a leopard, and a she-wolf—allegorical depictions of temptations towards sin) he cannot evade, and unable to find the "straight way" (diritta via) - also translatable as "right way" - to salvation (symbolized by the sun behind the mountain). Conscious that he is ruining himself and that he is falling into a "deep place" (basso loco) where the sun is silent ('l sol tace), Dante is at last rescued by Virgil, and the two of them begin their journey to the underworld. Each sin's punishment in Inferno is a contrapasso, a symbolic instance of poetic justice; for example, fortune-tellers have to walk forwards with their heads on backwards, unable to see what is ahead, because they tried to do so in life. Allegorically, the Inferno represents the Christian soul seeing sin for what it really is.

The Barque of Dante by Eugène Delacroix.

Dante passes through the gate of hell, which bears an inscription, the ninth (and final) line of which is the famous phrase "Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch'intrate", or "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here"[3] Before entering Hell completely, Dante and his guide see the Opportunists, souls of people who in life did nothing, neither for good nor evil (among these Dante recognizes either Pope Celestine V or Pontius Pilate; the text is ambiguous). Mixed with them are outcasts who took no side in the Rebellion of Angels. These souls are neither in Hell nor out of it, but reside on the shores of the Acheron, their punishment to eternally pursue a banner while pursued by wasps and hornets that continually sting them while maggots and other such insects drink their blood and tears. This symbolizes the sting of their conscience and the repugnance of sin.

Then Dante and Virgil reach the ferry that will take them across the river Acheron and to Hell. The ferry is piloted by Charon, who does not want to let Dante enter, for he is a living being. Virgil forces Charon to take him by means of another famous line Vuolsi così colà ove si puote (which translates to So it is wanted there where the power lies, referring to the fact that Dante is on his journey on divine grounds), but their passage across is undescribed since Dante faints and does not awake until he is on the other side.

The Circles of Hell

Virgil guides Dante through the nine circles of Hell. The circles are concentric, representing a gradual increase in wickedness, and culminating at the center of the earth, where Satan is held in bondage. Each circle's sinners are punished in a fashion fitting their crimes: each sinner is afflicted for all of eternity by the chief sin he committed. People who sinned but prayed for forgiveness before their deaths are found in Purgatory – where they labor to be free of their sins – not in Hell. Those in Hell are people who tried to justify their sins and are unrepentant. Furthermore, those in hell have knowledge of the past and future, but not of the present. This is a joke on them in Dante's mind because after the Final Judgment, time ends; those in Hell would then know nothing. The nine circles are:

First Circle (Limbo)

Here reside the unbaptized and the virtuous pagans, who, though not sinful, did not accept Christ. They are not punished in an active sense, but rather grieve only their separation from God, without hope of reconciliation. The chief irony in this circle is that Limbo shares many characteristics with the Elysian Fields; thus the guiltless damned are punished by living in a deficient form of Heaven. Without baptism ("the portal of faith," Canto IV, l.36) they lacked the hope for something greater than rational minds can conceive. Limbo includes green fields and a castle, the dwelling place of the wisest men of antiquity, including Virgil himself, as well as the Islamic philosophers Averroes and Avicenna. In the castle Dante meets the poets Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan and the philosophers Socrates and Aristotle. Interestingly, he also sees Saladin in Limbo (Canto IV). Dante implies that all virtuous pagans find themselves here, although he later encounters two in heaven and one (Cato of Utica) in Purgatory.

Beyond the first circle, all of those condemned for active, deliberately willed sin are judged by Minos, who sentences each soul to one of the lower eight circles by wrapping his tail around himself a corresponding number of times. The lower circles are structured according to the classical (Aristotelian) conception of virtue and vice, so that they are grouped into the sins of incontinence, violence, and fraud (which for many commentators are represented by the leopard, lion, and she-wolf[4]). The sins of incontinence — weakness in controlling one's desires and natural urges — are the mildest among them, and, correspondingly, appear first:

Gustave Doré, from his illustrations to the Divine Comedy (1857): Dante faints at the pitifulness of Francesca da Rimini's plight, while the hurricane of souls that she and her lover are trapped in surround the scene.

Second Circle

Those overcome by lust are punished in this circle. They are the first ones to be truly punished in Hell. These souls are blown about to and fro by a violent storm, without hope of rest. This symbolizes the power of lust to blow one about needlessly and aimlessly. Dante is informed by Francesca da Rimini of how she and her husband's brother Paolo committed adultery and died a violent death at the hands of her husband (Canto V).

Third Circle

Cerberus guards the gluttons, forced to lie in a vile slush made by freezing rain, black snow, and hail. This symbolizes the garbage that the gluttons made of their lives on earth, slavering over food. Dante converses with a Florentine contemporary identified as Ciacco ("Hog" — probably a nickname) regarding strife in Florence and the fate of prominent Florentines (Canto VI).

Fourth Circle

Those whose concern for material goods deviated from the desired mean are punished in this circle. They include the avaricious or miserly, who hoarded possessions, and the prodigal, who squandered them. Guarded by Plutus, the miserly group pushes great rocks towards the center of the circle; the wasters must take the rocks back to their own side of the circle (Canto VII). This is an antithetical punishment; the sinners must do the opposite of the actions they carried out in life. (In Gustave Doré's illustrations for this scene, the damned push huge money bags.)

The Stygian Lake, with the Ireful Sinners Fighting

William Blake

Fifth Circle

In the swamp-like water of the river Styx, the wrathful fight each other on the surface, and the sullen or slothful lie gurgling beneath the water. Phlegyas reluctantly transports Dante and Virgil across the Styx in his skiff. On the way they are accosted by Filippo Argenti, a Black Guelph from a prominent family (Cantos VII and VIII).

The lower parts of hell are contained within the walls of the city of Dis, which is itself surrounded by the Stygian marsh. Punished within Dis are active (rather than passive) sins. The walls of Dis are guarded by fallen angels. Virgil is unable to convince them to let Dante and him enter, and the Furies and Medusa threaten Dante. An angel sent from Heaven secures entry for the poets (Cantos VIII and IX).

Lower Hell, inside the walls of Dis, in an illustration by Stradanus. There is a drop from the sixth circle to the three rings of the seventh circle, then again to the ten rings of the eighth circle, and, at the bottom, to the icy ninth circle.

Sixth Circle

Heretics are trapped in flaming tombs. Dante holds discourse with a pair of Florentines in one of the tombs: Farinata degli Uberti, a Ghibelline; and Cavalcante de' Cavalcanti, a Guelph who was the father of Dante's friend and fellow poet Guido Cavalcanti (Cantos X and XI). The followers of Epicurus are also located here (Canto X).

Seventh Circle

This circle houses the violent. Its entry is guarded by the Minotaur, and it is divided into three rings:

- Outer ring, housing the violent against people and property, who are immersed in Phlegethon, a river of boiling blood, to a level commensurate with their sins. The Centaurs, commanded by Chiron, patrol the ring, firing arrows into those trying to escape. The centaur Nessus guides the poets along Phlegethon and across a ford in the river (Canto XII). This passage may have been influenced by the early medieval Visio Karoli Grossi.[5]

- Middle ring: In this ring are the suicides, who are transformed into gnarled thorny bushes and trees. They are torn at by the Harpies. Unique among the dead, the suicides will not be bodily resurrected after the final judgment, having given their bodies away through suicide. Instead they will maintain their bushy form, with their own corpses hanging from the limbs. Dante breaks a twig off one of the bushes and hears the tale of Pier delle Vigne, who committed suicide after falling out of favor with Emperor Frederick II. The other residents of this ring are the profligates, who destroyed their lives by destroying the means by which life is sustained (i.e. money and property). They are perpetually chased by ferocious dogs through the thorny undergrowth. (Canto XIII) The trees are a metaphor; in life the only way of the relief of suffering was through pain (i.e. suicide) and in Hell, the only form of relief of the suffering is through pain (breaking of the limbs to bleed).

- Inner ring: The violent against God (blasphemers), the violent against nature (sodomites), and the violent against order (usurers), all reside in a desert of flaming sand with fiery flakes raining from the sky. The blasphemers lie on the sand, the usurers sit, and the sodomites wander about in groups. Dante converses with two Florentine sodomites from different groups. One of them is Dante's mentor, Brunetto Latini. Dante is very surprised and touched by this encounter and shows Brunetto great respect for what he has taught him. The other is Iacopo Rusticucci, a politician. (Cantos XIV through XVI) Those punished here for usury include Florentines Catello di Rosso Gianfigliazzi, Ciappo Ubriachi, and Giovanni di Buiamonte, and Paduans Reginaldo degli Scrovegni and Vitaliano di Iacopo Vitaliani.

Eighth Circle

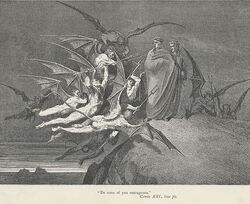

Dante's guide rebuffs Malacoda and his fiends between bolgie five and six in the Eighth Circle of Hell, Inferno, Canto 21.

Dante climbs the flinty steps in bolgia seven in the Eighth Circle of Hell, Inferno, Canto 26.

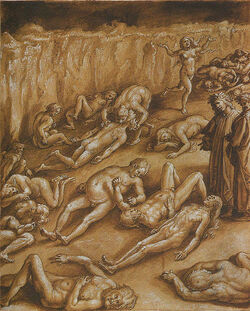

The falsifiers, who thrive in a diseased society, are now themselves diseased, Inferno, Canto 30.

The last two circles of Hell punish sins that involve conscious fraud or treachery. The circles can be reached only by descending a vast cliff, which Dante and Virgil do on the back of Geryon, a winged monster represented by Dante as having the face of an honest man and a body that ends in a scorpion-like stinger (Canto XVII).

The fraudulent—those guilty of deliberate, knowing evil—are located in a circle named Malebolge ("Evil Pockets"), divided into ten bolgie, or ditches of stone, with bridges spanning the ditches:

- Bolgia 1: Panderers (pimps) and seducers march in separate lines in opposite directions, whipped by demons. Just as they misled others in life, they are driven to march by demons for all eternity. In the group of panderers the poets notice Venedico Caccianemico, who sold his own sister to the Marchese d'Este, and in the group of seducers Virgil points out Jason (Canto XVIII).

- Bolgia 2: Flatterers are steeped in human excrement. This is because their flatteries on earth were nothing but "a load of excrement" (Canto XVIII).

- Bolgia 3: Those who committed simony are placed head-first in holes in the rock, with flames burning on the soles of their feet (resembling an inverted baptism). One of them, Pope Nicholas III, denounces as simonists two of his successors, Pope Boniface VIII and Pope Clement V (Canto XIX).

- Bolgia 4: Sorcerers and false prophets have their heads twisted around on their bodies backward. In addition, they cry so many tears that they cannot see. This is symbolic because these people tried to see into the future by forbidden means (and possibly retribution for the delusions they concocted that probably led their followers to their own perils); thus in Hell they can only see what is behind them and cannot see forward (Canto XX).

- Bolgia 5: Corrupt politicians (barrators) are immersed in a lake of boiling pitch, which represents the sticky fingers and dark secrets of their corrupt deals. They are guarded by devils called the Malebranche ("Evil Claws"). Their leader, Malacoda ("Evil Tail"), assigns a troop to escort Virgil and Dante to the next bridge. The troop hook and torment one of the sinners (identified by early commentators as Ciampolo), who names some Italian grafters and then tricks the Malebranche in order to escape back into the pitch. (Cantos XXI through XXIII)

- Bolgia 6: The bridge over this bolgia is broken: the poets climb down into it and find the Hypocrites listlessly walking along wearing gilded lead cloaks. Dante speaks with Catalano and Loderingo, members of the Jovial Friars. It is also ironic in this canto that while in the company of hypocrites, the poets also discover that the guardians of the fraudulent (the malebranche) are hypocrites themselves, as they find that they have lied to them, giving false directions, when at the same time they are punishing liars for similar sins. (Canto XXIII)

- Bolgia 7: Thieves, guarded by the centaur (as Dante describes him) Cacus, are pursued and bitten by snakes and lizards. The snake bites make them undergo various transformations, with some resurrected after being turned to ashes, some mutating into new creatures, and still others exchanging natures with the reptiles, becoming lizards themselves that chase the other thieves in turn. Just as the thieves stole other people's substance in life, and because thievery is reptilian in its secrecy, the thieves' substance is eaten away by reptiles and their bodies are constantly stolen by other thieves. (Cantos XXIV and XXV)

- Bolgia 8: Fraudulent advisors are encased in individual flames. Dante includes Ulysses and Diomedes together here for their role in the Trojan War. Ulysses tells the tale of his fatal final voyage (an invention of Dante's), where he left his home and family to sail to the end of the Earth. He equated life as a pursuit of knowledge that humanity can attain through effort, and in his search God sank his ship outside of Mount Purgatory. This symbolizes the inability of the individual to carve out one's own salvation. Instead, one must be totally subservient to the will of God and realize the inability of one to be a God unto oneself. Guido da Montefeltro recounts how his advice to Pope Boniface VIII resulted in his damnation, despite Boniface's promise of absolution. (Cantos XXVI and XXVII)

- Bolgia 9: A sword-wielding demon hacks at the sowers of discord. As they make their rounds the wounds heal, only to have the demon tear apart their bodies again. "See how I rend myself! How mutilated, see, is Mahomet; In front of me doth Ali weeping go, Cleft in the face from forelock unto chin; And all the others whom thou here beholdest, Disseminators of scandal and of schism. While living were, and therefore are cleft thus." Muhammad tells Dante to warn the schismatic and heretic Fra Dolcino (Cantos XXVIII and XXIX). Dante writes of Muhammad as a schismatic,[6][7] apparently viewing Islam as an off-shoot from Christianity, and similarly Dante seems to condemn Ali for schism between Sunni and Shiite.

- Bolgia 10: Here various sorts of falsifiers (alchemists, counterfeiters, perjurers, and impersonators), who are a disease on society, are themselves afflicted with different types of diseases (Cantos XXIX and XXX). Potiphar's wife is briefly mentioned here for her false accusation of Joseph. In the notes on her translation, Dorothy L. Sayers remarks that Malebolge "began with the sale of the sexual relationship, and went on to the sale of Church and State; now, the very money is itself corrupted, every affirmation has become perjury, and every identity a lie; no medium of exchange remains."[8]

Ninth Circle

- See also: Ugolino and Dante

Dante speaks to the traitors in the ice, Inferno, Canto 32.

The Ninth Circle is ringed by classical and Biblical giants. The giants are standing either on, or on a ledge above, the ninth circle of Hell, and are visible from the waist up at the ninth circle of the Malebolge. The giant Antaeus lowers Dante and Virgil into the pit that forms the ninth circle of Hell. (Canto XXXI) Traitors, distinguished from the "merely" fraudulent in that their acts involve betraying one in a special relationship to the betrayer, are frozen in a lake of ice known as Cocytus. Each group of traitors is encased in ice to a different depth, ranging from only the waist down to complete immersion. The circle is divided into four concentric zones:

- Round 1: Caïna, named for Cain, is home to traitors to their kindred. The souls here are immersed in the ice up to their necks. (Canto XXXII)

- Round 2: Antenora is named for Antenor of Troy, who according to medieval tradition betrayed his city to the Greeks. Traitors to political entities, such as party, city, or country, are located here. Count Ugolino pauses from gnawing on the head of his rival Archbishop Ruggieri to describe how Ruggieri imprisoned and starved him and his children. The souls here are immersed at almost the same level as those in Caïna, except they are unable to bend their necks. (Cantos XXXII and XXXIII)

- Round 3: Ptolomæa is probably named for Ptolemy, the captain of Jericho, who invited Simon Maccabaeus and his sons to a banquet and then killed them. Traitors to their guests are punished here. Fra Alberigo explains that sometimes a soul falls here before the time that Atropos (the Fate who cuts the thread of life) should send it. Their bodies on Earth are immediately possessed by a fiend. The souls here are immersed so much that only half of their faces are visible. As they cry, their tears freeze and seal their eyes shut–they are denied even the comfort of tears. (Canto XXXIII)

- Round 4: Judecca, named for Judas the Iscariot, Biblical betrayer of Christ, is for traitors to their lords and benefactors. All of the sinners punished within are completely encapsulated in ice, distorted to all conceivable positions.

Satan is trapped in the frozen central zone in the Ninth Circle of Hell, Inferno, Canto 34.

Dante and Virgil, with no one to talk to, quickly move on to the center of hell. Condemned to the very center of hell for committing the ultimate sin (treachery against God) is Satan, who has three faces, one red, one black, and one a pale yellow, each having a mouth that chews on a prominent traitor. Satan himself is represented as a giant, terrifying beast, weeping tears from his six eyes, which mix with the traitors' blood sickeningly. He is waist deep in ice, and beats his six wings as if trying to escape, but the icy wind that emanates only further ensures his imprisonment (as well as that of the others in the ring). The sinners in the mouths of Satan are Brutus and Cassius in the left and right mouths, respectively. They were involved in the assassination of Julius Caesar—an act which, to Dante, represented the destruction of a unified Italy. In the central, most vicious mouth is Judas Iscariot—the namesake of this zone and the betrayer of Jesus. Judas is being administered the most horrifying torture of the three traitors, his head in the mouth of Lucifer, and his back being forever skinned by the claws of Lucifer. (Canto XXXIV) What is seen here is a perverted trinity. Satan is impotent, ignorant, and evil while God can be attributed as the opposite: all powerful, all knowing, and good. The two poets escape by climbing down the ragged fur of Lucifer, passing through the center of the earth, emerging in the other hemisphere just before dawn on Easter Sunday beneath a sky studded with stars.

Purgatorio

Dante gazes at Mount Purgatory in an allegorical portrait by Agnolo Bronzino, painted circa 1530.

Plan of Mount Purgatory. As with Paradise, the structure is of the form 2+7+1=9+1=10, with one of the ten regions different in nature from the other nine.

Having survived the depths of Hell, Dante and Virgil ascend out of the undergloom, to the Mountain of Purgatory on the far side of the world (in Dante's time, it was believed that Hell existed underneath Jerusalem). The Mountain is on an island, the only land in the Southern Hemisphere, created with earth taken from the excavation of hell. At the shores of Purgatory, Dante and Virgil are attracted by a musical performance by Casella, but are reprimanded by Cato, a pagan who has been placed by God as the general guardian of the approach to the mountain. The text gives no indication whether or not Cato's soul is destined for heaven: his symbolic significance has been much debated. (Cantos I and II).

Allegorically, the Purgatorio represents the Christian life. Christian souls arrive escorted by an angel, singing in exitu Israel de Aegypto. In his Letter to Cangrande, Dante explains that this reference to Israel leaving Egypt refers both to the redemption of Christ and to "the conversion of the soul from the sorrow and misery of sin to the state of grace."[9] Appropriately, therefore, it is Easter Sunday when Dante and Virgil arrive.

The Purgatorio is notable for demonstrating the medieval knowledge of a spherical Earth. During the poem, Dante discusses the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the sun, and the various timezones of the Earth. At this stage it is, Dante says, sunset at Jerusalem, midnight on the River Ganges, and sunrise in Purgatory.

Dante starts the ascent of Mount Purgatory at sunrise. On the lower slopes (designated as "ante-Purgatory" by commentators) Dante meets first a group of excommunicates, detained for a period thirty times as long as their period of contumacy. Ascending higher, he encounters those too lazy to repent until shortly before death, and those who suffered violent deaths (often due to leading extremely sinful lives). These souls will be admitted to Purgatory thanks to their genuine repentance, but must wait outside for an amount of time equal to their lives on earth (Cantos III through VI). Finally, Dante is shown a beautiful valley where he sees the lately deceased monarchs of the great nations of Europe, and a number of other persons whose devotion to public and private duties hampered their faith (Cantos VII and VIII). Dante's beautiful description of evening in this valley (Canto VIII) was the inspiration for a similar passage in Byron's Don Juan.[10] From this valley Dante is carried (while asleep) up to the gates of Purgatory proper (Canto IX).

The gate of Purgatory is guarded by an angel who uses the point of his sword to draw the letter "P" (signifying peccatum, sin) seven times on Dante's forehead, bidding him to "wash you those wounds within." The angel uses two keys, silver (remorse) and gold (reconciliation) to open the gate – both are necessary.[11] The angel at the gate then warns Dante not to look back, lest he should find himself outside the gate again, symbolizing Dante having to overcome and rise above the hell that he has just left and thusly leaving his sinning ways behind him.

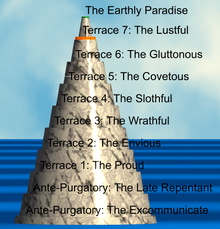

From there, Virgil guides the pilgrim Dante through the seven terraces of Purgatory. These correspond to the seven deadly sins, each terrace purging a particular sin in an appropriate manner. Those in purgatory can leave their circle whenever they like, but essentially there is an honor system where no one leaves until they have corrected the nature within themselves that caused them to commit that sin. Souls can only move upwards and never backwards, since the intent of Purgatory is for souls to ascend towards God in Heaven, and can ascend only during daylight hours, since the light of God is the only true guidance.

Associated with each terrace are historical and mythological examples of the relevant deadly sin and of its opposite virtue, together with an appropriate prayer and beatitude.

The Terraces of Purgatory

In an example of humility, the Emperor Trajan stops to render justice to a poor widow, Purgatorio, Canto 10

On the first three terraces of Purgatory are purified those whose sins were caused by perverted love directed towards actual harm of others.

- First Terrace. The proud are purged by carrying giant stones on their backs, unable to stand up straight (Cantos X through XII). This teaches the sinner that pride puts weight on the soul and it is better to throw it off. Furthermore, there are carvings of historical and mythological examples of pride and humility to learn from. With the weight on one's back, one cannot help but see this carved pavement and learn from it. The prayer for this terrace is the Lord's Prayer, and the beatitude is blessed are the poor in spirit. At the ascent to the next terrace, an angel clears a letter P from Dante's head. This process is repeated on each terrace. Each time a P is removed, Dante's body feels lighter, because he becomes less and less weighed down by sin.

- Second Terrace. The envious are purged by having their eyes sewn shut and wearing clothing that makes the soul indistinguishable from the ground (Cantos XIII through XV). This is akin to a falconer's sewing the eyes of a falcon shut in order to train it. In this regard, God is the falconer and is training the souls not to envy others and to direct their love towards Him. Two examples of envy (Cain who was jealous of his brother, and Aglauros who was jealous of her sister) are contrasted with three of generosity. Because the souls here cannot see, the examples are voices on the air, including Jesus' words "love your enemies." As he is leaving the terrace, the dazzling light of the angel causes Dante to observe that the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection "as theory and experiment will show."[12] The beatitude for this terrace is blessed are the merciful.

- Third Terrace. The wrathful are purged by walking around in acrid smoke (Cantos XV through XVII). Souls correct themselves by learning how wrath has blinded their vision, impeding their judgment (the sin of wrath represents a perversion of the natural love of justice). The prayer for this terrace is the Agnus Dei, and the beatitude is blessed are the peacemakers.

On the fourth terrace we find sinners whose sin was that of deficient love—that is, sloth or acedia.

- Fourth Terrace. The slothful are purged by continually running (Cantos XVIII and XIX). Those who were slothful in life can only purge this sin by being zealous in their desire for penance. Allegorically, spiritual laziness and lack of caring lead to sadness, and so the beatitude for this terrace is blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted.[13]

On the fifth through seventh terraces are those who sinned by loving good things, but loving them in a disordered way.

- Fifth Terrace. The avaricious and prodigal are purged by lying face-down on the ground, unable to move (Cantos XIX through XXI). Excessive concern for earthly goods—whether in the form of greed or extravagance—is punished and purified. The sinner learns to turn his desire from possessions, power or position to God. It is here that the poets meet the soul of Statius, who has completed his purgation and joins them on their ascent to paradise.

- Sixth Terrace. The gluttonous are purged by abstaining from any food or drink (Cantos XXII through XXIV). Here, the soul's desire to eat a forbidden fruit causes its shade to starve. To sharpen the pains of hunger, the former gluttons on this terrace are forced to pass by cascades of cool water without stopping to drink. (Considering Dante's use of Greek myth, this may be inspired by Tantalus.)

- Seventh Terrace. The lustful are purged by burning in an immense wall of flame (Cantos XXV through XXVII). All of those who committed sexual sins, both heterosexual and homosexual, are purified by the fire. Excessive sexual desire misdirects one's love from God and this terrace is meant to correct that. In addition, perhaps because all sin has its roots in misguided love, every soul who has completed his penance on the lower six cornices must pass through the wall of flame before ascending to the Earthly Paradise. Here Dante, too, must share the penance of the redeemed as the last "P" is removed from his forehead.

Dante's meeting with Matelda, lithograph by Cairoli (1889)

The ascent of the mountain culminates at the summit, which is in fact the Garden of Eden (Cantos XXVIII through XXXIII). This place is meant to return one to a state of innocence that existed before the sin of Adam and Eve caused the fall from grace. Here Dante meets Matelda, a woman of grace and beauty who prepares souls for their ascent to heaven. With her Dante witnesses a highly symbolic procession that may be read as an allegorical masque of the Church and the Sacrament. The procession forms an allegory within the allegory, somewhat like Shakespeare's play within a play. One participant in the procession is Beatrice, whom Dante loved in childhood, and at whose request Virgil was commissioned to bring Dante on his journey.

Dante's meeting with Beatrice, by John William Waterhouse

Virgil, as a pagan, is a permanent denizen of Limbo, the first circle of Hell, and may not enter Paradise; he vanishes. Beatrice then becomes the second guide, and will accompany Dante in his vision of Heaven.

Dante drinks from the River Lethe, which causes the soul to forget past sins, and then from the River Eunoë, which effects the renewal of memories of good deeds. Thus purified, souls can direct their love fully towards God to the best of their inherent capability to do so. They are then ready to leave Mount Purgatory for Paradise. Being totally purged of sin, Purgatorio ends with Dante's vision aimed at the stars, anticipating his ascent to heaven.

Paradiso

Dante and Beatrice speak to Piccarda and Constance of Sicily, in a fresco by Philipp Veit, Paradiso, Canto 3

After an initial ascension (Canto I), Beatrice guides Dante through the nine celestial spheres of Heaven. These are concentric and spherical, similar to Aristotelian and Ptolemaic cosmology. Dante admits that the vision of heaven he receives is the one that his human eyes permit him to see. Thus, the vision of heaven found in the Cantos is Dante's own personal vision, ambiguous in its true construction. The addition of a moral dimension means that a soul that has reached Paradise stops at the level applicable to it. Souls are allotted to the point of heaven that fits with their human ability to love God. Thus, there is a heavenly hierarchy. All parts of heaven are accessible to the heavenly soul. That is to say all experience God but there is a hierarchy in the sense that some souls are more spiritually developed than others. This is not determined by time or learning as such but by their proximity to God (how much they allow themselves to experience Him above other things). It must be remembered in Dante's schema that all souls in Heaven are on some level always in contact with God.

While the structures of the Inferno and Purgatorio were based around different classifications of sin, the structure of the Paradiso is based on the four cardinal virtues and the three theological virtues.

The Spheres of Heaven

The nine spheres are:

- First Sphere. The sphere of the Moon is that of souls who abandoned their vows, and so were deficient in the virtue of fortitude (Cantos II through V). Dante meets Piccarda, sister of Dante's friend Forese Donati, who died shortly after being forcibly removed from her convent. Beatrice discourses on the freedom of the will, and the inviolability of sacred vows.

- Second Sphere. The sphere of Mercury is that of souls who did good out of a desire for fame, but who, being ambitious, were deficient in the virtue of justice (Cantos V through VII). Justinian recounts the history of the Roman Empire. Beatrice explains to Dante the atonement of Christ for the sins of humanity.

Folquet de Marseilles bemoans the corruption of the Church, in a miniature by Giovanni di Paolo, Paradiso, Canto 9

- Third Sphere. The sphere of Venus is that of souls who did good out of love, but were deficient in the virtue of temperance (Cantos VIII and IX). Dante meets Charles Martel of Anjou, who decries those who adopt inappropriate vocations, and Cunizza da Romano. Folquet de Marseilles points out Rahab, the brightest soul among those of this sphere, and condemns the city of Florence for producing that "cursed flower" (the florin) which is responsible for the corruption of the Church.

Illustration of Dante's Paradiso, showing Thomas Aquinas and 11 other teachers of wisdom in the sphere of the Sun, by Giovanni di Paolo (between 1442 and c.1450)

- Fourth Sphere. The sphere of the Sun is that of souls of the wise, who embody prudence (Cantos X through XIV). Dante is addressed by St. Thomas Aquinas, who recounts the life of St. Francis of Assisi and laments the corruption of his own Dominican Order. Dante is then met by St. Bonaventure, a Franciscan, who recounts the life of St. Dominic, and laments the corruption of the Franciscan Order. The two orders were not always friendly on earth, and having members of one order praising the founder of the other shows the love present in Heaven. Dante arranges the wise into two rings of twelve; his choices of who to include give his assessment of the significant philosophers of medieval times. Finally, Aquinas introduces King Solomon, who answers Dante's question about the doctrine of the resurrection of the body.

- Fifth Sphere. The sphere of Mars is that of souls who fought for Christianity, and who embody fortitude (Cantos XIV through XVIII). The souls in this sphere form an enormous cross. Dante speaks with the soul of his ancestor Cacciaguida, who praises the former virtues of the residents of Florence, recounts the rise and fall of Florentine families and foretells Dante's exile from Florence, before finally introducing some notable warrior souls (among them Joshua, Roland, Charlemagne, and Godfrey of Bouillon).

- Sixth Sphere. The sphere of Jupiter is that of souls who personified justice, something of great concern to Dante (Cantos XVIII through XX). The souls here spell out the Latin for "Love justice, ye that judge the earth," and then arrange themselves into the shape of an imperial eagle. Present here are David, Hezekiah, Trajan (converted to Christianity according to a medieval legend), Constantine, William II of Sicily, and (Dante is amazed at this) Rhipeus the Trojan, saved by the mercy of God.

- Seventh Sphere. The sphere of Saturn is that of the contemplatives, who embody temperance (Cantos XXI and XXII). Dante here meets Peter Damian, and discusses with him monasticism, the doctrine of predestination, and the sad state of the Church. Beatrice, who represents theology, becomes increasingly lovely here, indicating the contemplative's closer insight into the truth of God.

- Eighth Sphere. The sphere of fixed stars is the sphere of the Church Triumphant (Cantos XXII through XXVII). Here, Dante sees visions of Christ and of the Virgin Mary. He is tested on faith by Saint Peter, hope by Saint James, and love by Saint John the Evangelist. Dante justifies his medieval belief in astrology, that the power of the constellations is drawn from God.

Dante and Beatrice see God as a point of light surrounded by angels; from Gustave Doré's illustrations for the Divine Comedy, Paradiso, Canto 28

- Ninth Sphere. The Primum Mobile ("first moved" sphere) is the abode of angels (Cantos XXVII through XXIX). Dante sees God as a point of light surrounded by nine rings of angels, and is told about the creation of the universe.

From the Primum Mobile, Dante ascends to a region beyond physical existence, called the Empyrean (Cantos XXX through XXXIII). Here the souls of all the believers form the petals of an enormous rose. Here, Beatrice leaves Dante with Saint Bernard, because theology has reached its limits. Saint Bernard prays to Mary on behalf of Dante. Finally, Dante comes face-to-face with God Himself, and is granted understanding of the Divine and of human nature. His vision is improved beyond that of human comprehension. God appears as three equally large circles within each other representing the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit with the essence of each part of God, separate yet one. The book ends with Dante trying to understand how the circles fit together, how the Son is separate yet one with the Father but as Dante put it "that was not a flight for my wings" and the vision of God becomes equally inimitable and inexplicable that no word or intellectual exercise can come close to explaining what he saw. Dante's soul, through God's absolute love, experiences a unification with itself and all things "but already my desire and my will were being turned like a wheel, all at one speed by the Love that turns the sun and all the other stars".

Earliest manuscripts

Detail of a manuscript in Milan's Biblioteca Trivulziana (MS 1080), written in 1337 by Francesco di ser Nardo da Barberino, showing the beginning of Dante's Comedy.

According to the Società Dantesca Italiana, no original manuscript written by Dante has survived, though there are many manuscript copies from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (more than 825 are listed on their site [2]). The oldest belongs to the 1330s, almost a decade after Dante's death. The most precious ones are the three full copies made by Giovanni Boccaccio (1360s), who himself did not have the original manuscript as a source.

The first printed edition was published in Foligno, Italy, by Johann Numeister and Evangelista Angelini on 11 April 1472. Of the 300 copies printed, fourteen still survive. The original printing press is on display in the Oratorio della Nunziatella in Foligno.

Printing press of the first printed edition

Thematic concerns

The Divine Comedy can be described simply as an allegory: Each canto, and the episodes therein, can contain many alternative meanings. Dante's allegory, however, is more complex, and, in explaining how to read the poem (see the Letter to Cangrande [3]), he outlines other levels of meaning besides the allegory (the historical, the moral, the literal, and the anagogical).

The structure of the poem, likewise, is quite complex, with mathematical and numerological patterns arching throughout the work, particularly threes and nines. The poem is often lauded for its particularly human qualities: Dante's skillful delineation of the characters he encounters in Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise; his bitter denunciations of Florentine and Italian politics; and his powerful poetic imagination. Dante's use of real characters, according to Dorothy Sayers in her introduction to her translation of "L'Inferno", allows Dante the freedom of not having to involve the reader in description, and allows him to "[make] room in his poem for the discussion of a great many subjects of the utmost importance, thus widening its range and increasing its variety."

Dante called the poem "Comedy" (the adjective "Divine" added later in the 14th century) because poems in the ancient world were classified as High ("Tragedy") or Low ("Comedy"). Low poems had happy endings and were of everyday or vulgar subjects, while High poems were for more serious matters. Dante was one of the first in the Middle Ages to write of a serious subject, the Redemption of man, in the low and vulgar Italian language and not the Latin language as one might expect for such a serious topic. Boccaccio's account that an early version of the poem was begun by Dante in Latin is still controversial.[14][15]

Renaissance Humanist Thematic Elements

Even though Dante is considered a medieval, as opposed to a renaissance, writer, the Divine Comedy translates the metaphysical into physical terms. This emphasis of sin’s and religion’s effect on humanity in present terms as opposed to medieval thought emphasizing the eschatological effect on souls makes Dante one of the first elucidators of elements of renaissance humanism.[16] Furthermore, Dante’s emphasis on ancient Greek and Roman myths, philosophies, and works is typical of a Renaissance syncretistic strain that generally was not typical of medieval thought.

While Dante’s citation of ancient works is readily apparent, his emphasis on the eschatological and present day effects of sin and piousness have only recently been explored by scholars such as William Cook and Ron Herzman.[17] As a brief illustration of the point, one renaissance humanist theme in the Divine Comedy can be found in the first section of the Inferno where Dante shares with the damned fleshy sins, as opposed to the more grievous willful sins found in the lower circles of Hell.

- At the shores of Acheron outside of Hell where those who did not choose to lead virtuous or overtly sinful lives are punished, Dante shares their sin by taking no stance for or against the sinners. Instead, he is saddened by the damned’s pitiful state.

- At the first circle where the virtuous pagans who pursued honor above all else are punished by eternally knowing they have fallen short for their lack of faith, Dante shares with them their love of honor, as evidenced by the word “honor” being used repeatedly in the Canto.

- At the second circle where the lustful are punished for their adultery, Dante’s emotions and physical actions (such as him fainting) are equally intemperate.

- At the third circle where Ciacco and other gluttons are punished for their appetites, Dante’s appetite for political information about times in the future is equally gluttonous.

- At the fourth circle where avarice is punished, Dante is equally avaricious in his desire to spend all his time admiring the people he sees and information from Virgil (who reminds Dante his questions are “vain”) instead of showing disdain for those punished for that sin.

- At the fifth circle where the wrathful are punished, Dante angrily condemns Filippo Argenti by displaying his own wrath, and cannot help but to stare at Medusa representing worldly sin. It should be noted that commentators have argued that Dante's wrath was not sinful at all, but instead in medieval times was virtuous as it was directed against sin.[18]

- At the sixth circle where heretics are punished (who are not coincidentally Florentine partisans), Dante shares with them an unnecessary degree of political concerns as opposed to religious concerns (which compares nicely with the Greek materialists such as Epicurus punished there for their purely secular worldview).

The Divine Comedy and Islamic philosophy

In 1919 Professor Miguel Asín Palacios, a Spanish scholar and a Catholic priest, published La Escatología musulmana en la Divina Comedia ("Islamic Eschatology in the Divine Comedy"), an account of parallels between early Islamic philosophy and the Divine Comedy. Palacios argued that Dante derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter indirectly from the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi and from the Isra and Mi'raj or night journey of Muhammad to heaven. The latter is described in the Hadith and the Kitab al Miraj (translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly before[19] as Liber Scale Machometi, "The Book of Muhammad's Ladder"), and has some slight similarities to the Paradiso, such as a seven-fold division of Paradise.[20]

Dante lived in a Europe of substantial literary and philosophical contact with the Muslim world, encouraged by such factors as Averroism and the patronage of Alfonso X of Castile. Of the twelve wise men Dante meets in Canto X of the Paradiso, Thomas Aquinas and, even more so, Sigier of Brabant were strongly influenced by Arabic commentators on Aristotle.[21] Medieval Christian mysticism also shared the Neoplatonic influence of Sufis such as Ibn Arabi. Philosopher Frederick Copleston argued in 1950 that Dante's respectful treatment of Averroes, Avicenna, and Sigier of Brabant indicates his acknowledgement of a "considerable debt" to Islamic philosophy.[22]

Although this philosophical influence is generally acknowledged, many scholars have not been satisfied that Dante was influenced by the Kitab al Miraj. The twentieth century Orientalist Francesco Gabrieli expressed skepticism regarding the claimed similarities, and the lack of evidence of a vehicle through which it could have been transmitted to Dante. Even so, while dismissing the probability of some influences posited in Palacios' work, Gabrieli recognized that it was "at least possible, if not probable, that Dante may have known the Liber scalae and have taken from it certain images and concepts of Muslim eschatology".[citation needed] Shortly before her death the Italian philologist Maria Corti pointed out that, during his stay at the court of Alfonso X, Dante's mentor Brunetto Latini met Bonaventura de Siena, a Tuscan who had translated the Liber scalae from Arabic into Latin. According to Corti,[23] Brunetto may have provided a copy of that work to Dante, though there is no evidence that this occurred.

Literary influence in the English-speaking world and beyond

The work was not always so well regarded. After being recognized as a masterpiece in the first centuries following its publication,[24] the work was largely ignored during the Enlightenment, with some notable exceptions such as Vittorio Alfieri, Antoine de Rivarol, who translated the Inferno into French, and Giambattista Vico, who in the Scienza nuova and in the Giudizio su Dante inaugurated what would later become the romantic reappraisal of Dante, juxtaposing him to Homer[25]. The Comedy was "rediscovered" by William Blake - who illustrated several passages of the epic - and the romantic writers of the 19th century. Later authors such as T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Samuel Beckett, and James Joyce have drawn on it for inspiration. The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was its first American translator,[26] and modern poets, including Seamus Heaney,[27] Robert Pinsky, John Ciardi, and W. S. Merwin, have also produced translations of all or parts of the book. In Russia, beyond Pushkin's memorable translation of a few triplets, Osip Mandelstam's late poetry has been said to bear of the mark of a "tormented meditation" on the Comedy.[28] In 1934 Mandelstam gave a disturbingly modern reading of the poem in his labyrinthine "Conversation on Dante"[29] .

The Divine Comedy in the arts

- Main article: Dante and his Divine Comedy in popular culture

The Divine Comedy has been a source of inspiration for countless artists for almost seven centuries — as one of the most well known and greatest artistic works in the Western tradition, its influence on culture cannot be overstated.

See also

- Bangsian fantasy

- List of cultural references in The Divine Comedy

Footnotes

- ↑ Bloom, Harold (1994). The Western Canon. See also Western canon for other "canons" that include the Divine Comedy.

- ↑ See Lepschy, Laura; Lepschy, Giulio (1977). The Italian Language Today. or any other history of Italian language.

- ↑ There are many English translations of this famous line. Some examples include

- All hope abandon, ye who enter here - Henry Francis Cary (1805–1844)

- All hope abandon, ye who enter in! - Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1882)

- Leave every hope, ye who enter! - Charles Eliot Norton (1891)

- Leave all hope, ye that enter - Carlyle-Wicksteed (1932)

- Lay down all hope, you that go in by me. - Dorothy L. Sayers (1949)

- Abandon every hope, you who enter. - Charles S. Singleton (1970)

- Abandon all hope, ye who enter here - John Ciardi (1977)

- No room for hope, when you enter this place - C. H. Sisson (1980)

- Abandon every hope, who enter here. - Allen Mandelbaum (1982)

- Abandon all hope, you who enter here - Robert Pinsky (1993)

- Abandon every hope, all you who enter - Mark Musa (1995)

- Abandon every hope, you who enter. - Robert M. Durling (1996)

- All hope abandon, you who enter here. - James Finn Cotter (2000) [1]

- Abandon all hope upon entering here! - Marcus Saunders (2004)

- ↑ There is no general agreement on which animals represent the sins incontinence, violence, and fraud. Some see it as the she-wolf, lion, and leopard respectively, while others see it as the leopard, lion, and she-wolf respectively.

- ↑ The punishment of immersion was not typically ascribed in Dante's age to the violent, but the Visio attaches it to those who facere praelia et homicidia et rapinas pro cupiditate terrena ("make battle and murder and rapine because of worldly cupidity"). Theodore Silverstein (1936), "Inferno, XII, 100–126, and the Visio Karoli Crassi," Modern Language Notes, 51:7, 449–452, and ibid. (1939), "The Throne of the Emperor Henry in Dante's Paradise and the Mediaeval Conception of Christian Kingship," Harvard Theological Review, 32:2, 115–129, suggests that Dante's interest in contemporary politics would have attracted him to a piece like the Visio. Its popularity assures that Dante would have had access to it. Jacques Le Goff, Goldhammer, Arthur, tr. (1986), The Birth of Purgatory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0 226 47083 0), states definitively that ("we know [that]") Dante read it.

- ↑ Wallace Fowlie, A Reading of Dante's Inferno, University Of Chicago Press, 1981, p. 178.

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, Inferno, notes on Canto XXVIII.

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, Inferno, notes on Canto XXIX.

- ↑ "The Letter to Can Grande," in Literary Criticism of Dante Alighieri, translated and edited by Robert S. Haller (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1973), 99

- ↑ Byron, Don Juan, Canto 3, CVIII.

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory, notes on page 140.

- ↑ Purgatorio, XV, line 21, tr. Dorothy L. Sayers, 1955.

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory, notes on pages 209 and 222.

- ↑ Boccaccio also quotes the initial triplet:"Ultima regna canam fluvido contermina mundo, / spiritibus quae lata patent, quae premia solvunt /pro meritis cuicumque suis". For translation and more, see Guyda Armstrong, , Review of Giovanni Boccaccio. Life of Dante. J. G. Nichols, trans. London: Hesperus Press, 2002.

- ↑ Hiram Peri, The Original Plan of the Divine Comedy, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 18, No. 3/4 (1955), pp. 189-210.

- ↑ Margaret L. King, The Renaissance in Europe (Laurence King Publishing, 2003): 51.

- ↑ See Hell, Purgatory, Paradise: Dante's Divine Comedy by William R Cook and Ronald B Herzman.

- ↑ John D. Sinclair, Dante's Inferno: Italian Text With English Translation and Comment (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970): 118 to 119.

- ↑ I. Heullant-Donat and M.-A. Polo de Beaulieu, "Histoire d'une traduction," in Le Livre de l'échelle de Mahomet, Latin edition and French translation by Gisèle Besson and Michèle Brossard-Dandré, Collection Lettres Gothiques, Le Livre de Poche, 1991, p. 22 with note 37.

- ↑ See the English translation of the Kitab al Miraj. However, considering Dante's personal convictions, the political climate, lack of said books, and aparent hardships in transporting them to Europe- it is quite doubtful Dante had seen any of them, much less read them.

- ↑ Frederick Copleston (1950). A History of Philosophy, Volume 2. London: Continuum, 200.

- ↑ Frederick Copleston, op. cit.

- ↑ Maria Corti: Dante e l'Islam (interview)

- ↑ as Chaucer wrote in the Monk's Tale, "Redeth the grete poete of Ytaille / That highte Dant, for he kan al devyse / Fro point to point; nat o word wol he faille".

- ↑ Erich Auerbach,Dante: Poet of the Secular World. ISBN 0-226-03205-1.

- ↑ Irmscher, Christoph. Longfellow Redux. University of Illinois, 2008: 11. ISBN 9780252030635.

- ↑ see: Seamus Heaney, “Envies and Identifications: Dante and the Modern Poet.” The Poet’s Dante: Twentieth-Century Responses. Ed. Peter S. Hawkins and Rachel Jacoff. New York: Farrar, 2001. 239-258.

- ↑ Marina Glazova, Mandelstam and Dante: The Divine Comedy in Mandelstam's poetry of the 1930s Studies in East European Thought, Volume 28, Number 4, November, 1984.

- ↑ James Fenton, Hell set to music, The Guardian, 16 July 2005.

External links

- World of Dante Multimedia website that offers Italian text of Divine Comedy, Allen Mandelbaum's translation, gallery, interactive maps, timeline, musical recordings, and searchable database for students and teachers by Deborah Parker and IATH (Institute for Advanced Technologies in the Humanities) of the University of Virginia

- Princeton Dante Project Website that offers the complete text of the Divine Comedy (and Dante's other works) in Italian and English along with audio accompaniment in both languages. Includes historical and interpretive annotation.

- Dante Dartmouth Project: Full text of more than 70 Italian, Latin, and English commentaries on the Commedia, ranging in date from 1322 (Iacopo Alighieri) to the 2000s (Robert Hollander)

- Dante's Divine Comedy presented by the Electronic Literature Foundation. Multiple editions, with Italian and English facing page and interpolated versions.

- The Comedy in English: trans. Cary (with Doré's illustrations) (HTML), trans. Cary (with Doré's illustrations) (zipped HTML downloadable from Project Gutenberg), Cary/Longfellow/Mandelbaum parallel edition

- On-line Concordance to the Divine Comedy

- Audiobooks: Public domain recordings from LibriVox (in Italian, Longfellow translation); some additional recordings

- Wikisummaries summary and analysis of "Inferno"

- Danteworlds, multimedia presentation of the Divine Comedy for students by Guy Raffa of the University of Texas

- Dante's Places: a map (still a prototype) of the places named by Dante in the Commedia, created with GoogleMaps. An explanatory PDF is available for download at the same page